Surely you’ve seen some of these photos; if you’re a photographer, you’ve marveled over the ability of the photographer to get all those people to their proper positions, and you’ve wondered at the sheer creative genius required to set the photos up.

Like this one, a depiction of the Liberty Bell — composed of 25,000 officers and men at Fort Dix, New Jersey. The photo was taken in 1918.

The Carl Hammer Gallery in Chicago featured an exhibit of these monumental photos in April and May, 2007:

The Carl Hammer Gallery in Chicago featured an exhibit of these monumental photos in April and May, 2007:

The outbreak of World War I and its inherent violence engendered a new commitment by the world’s photographers to document every aspect of the fighting, ending an era of In A Patriotic Mole, A Living Photograph, Louis Kaplan, of Southern Illinois University, writes, “The so-called living photographs and living insignia of Arthur Mole [and John Thomas] are photo-literal attempts to recover the old image of national identity at the very moment when the United States entered the Great War in 1917.

Mole’s [and Thomas’s] photos assert, bolster, and recover the image of American national identity via photographic imaging. Moreover, these military formations serve as rallying points to support U.S. involvement in the war and to ward off any isolationist tendencies. In life during wartime, [their] patriotic images function as “nationalist propaganda” and instantiate photo cultural formations of citizenship for both the participants and the consumers of these group photographs.”

The monumentality of this project somewhat overshadows the philanthropic magnanimity of the artists themselves.Instead of prospering from the sale of the images produced, the artists donated the entire income derived to the families of the returning soldiers and to this country’s efforts to re-build their lives as a part of the re-entry process.

Eventually, other photographers, appeared on the scene, a bit later in time than the activity conducted by Mole and Thomas, but all were very clearly inspired by the creativity and monumentality of the duo’s production of the “Living” photograph.

One of the most notable of those artists was Eugene Omar Goldbeck. He specialized in the large scale group portrait and photographed important people (Albert Einstein), events, and scenes (Babe Ruth’s New York Yankees in his home town, San Antonio) both locally and around the world (Mt. McKinley). Among his military photographs, the Living Insignia projects are of particular significance as to how he is remembered.

Using a camera as an artist’s tool, using a literal army as a palette, using a parade ground as a sort of canvas, these photographers made some very interesting pictures. The Human Statue of Liberty, with 18,000 men at Camp Dodge, Iowa?

Most of these pictures were taken prior to 1930. Veterans who posed as part of these photos would be between 80 and 100 years old now. Are there veterans in your town who posed for one of these photos?

Good photographic copies of some of these pictures are available from galleries. They are discussion starters, that’s for sure.

Some questions for discussion:

- Considering the years of the photos, do you think many of these men saw duty overseas in World War I.

- Look at the camps, and do an internet search for influenza outbreaks in that era. Were any of these camps focal points for influenza?

- Considering the toll influenza took on these men, about how many out of each photo would have survived the influenza, on average?

- Considering the time, assume these men were between the ages of 18 and 25. What was their fate after the Stock Market Crash of 1929? Where were they during World War II?

- Do a search: Do these camps still exist? Can you find their locations on a map, whether they exist or not?

- Why do the critics say these photos might have been used to build national unity, and to cement national identity and will in time of war?

- What is it about making these photos that would build patriotism? Are these photos patriotic now?

These quirky photos are true snapshots in time. They can be used for warm-ups/bell ringers, or to construct lesson plans around.

Tip of the old scrub brush to Gil Brassard, a native, patriotic and corporate historian hiding in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

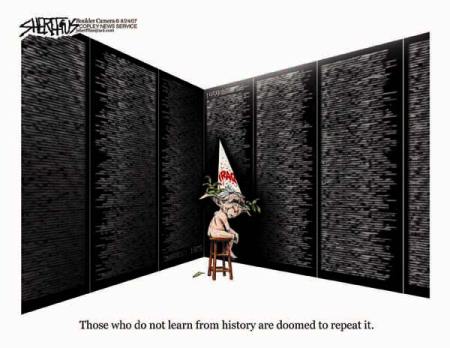

Spread the word; friends don't allow friends to repeat history.

Posted by Ed Darrell

Posted by Ed Darrell  The Carl Hammer Gallery in Chicago featured

The Carl Hammer Gallery in Chicago featured

Examples of some of the most famous cave and rock paintings populate the site, along with many lesser known creations — the eponymous paintings, the Bradshaw group, generally disappear from U.S. versions of world history texts.

Examples of some of the most famous cave and rock paintings populate the site, along with many lesser known creations — the eponymous paintings, the Bradshaw group, generally disappear from U.S. versions of world history texts.