Editor’s Note: I’m traveling this week, celebrating our independence 231 years on. While mostly out of pocket, I’ll feature some encore posts, material that deserves another look to keep it from fading from memory. This post, below, is the second of a two-part series from August 2006.

Bogus history infects political discussions more than others, though there are some areas where bogus history strays into the realm of science (false claims that Darwin and Pasteur recanted, for example).

1. The author pitches the claim directly to the media or to organizations of non-historians, for pay.

Historians are detectives, and they like to share what they find. One historian working in the papers of one figure from history will find a letter from another figure, and pass that information on to the historian working on the second figure. Historians teach history, write it up for scholarly work, and often spin it in more fascinating tales for popular work. Most years there are several good works competing for the Pulitzer Prize in history. Academic historians, those tied to universities and other teaching institutions, join societies, attend meetings, and write their material in journals — all pitched to sharing what they have learned.

Bogus historians tend to show up at conferences of non-historians. Douglas Stringfellow’s tales of World War II derring do were pitched to civic clubs, places where other historians or anyone else likely to know better, generally would not appear (Stringfellow’s stories of action behind enemy lines in World War II won him several speaking awards, and based on his war record, he was nominated to a seat in Congress for Utah, in 1952, which he won; a soldier who knew Stringfellow during the war happened through Salt Lake City during the 1954 re-election campaign, and revealed that Stringfellow’s exploits were contrived; he was forced to resign the nomination). Case in point: David Barton speaks more often to gun collectors than to history groups.

2. The author says that a powerful establishment is trying to suppress his or her work.

Sen. Joseph McCarthy insisted that anyone who opposed his claims that communists dominated certain government agencies, or that any given person was a communist, was because those who challenged him were, themselves, part of the greater conspiracy, trying to silence him. Utah Sen. Arthur V. Watkins, who chaired the committee that recommended censure for Sen. McCarthy, lost his own re-election campaign in 1958 in part to the belief by Utah voters that such a conspiracy existed and had succeeded in suppressing McCarthy.

But there was no organized campaign against McCarthy. Individual Americans, spurred by patriotism, the Boy Scout Law, or just a sense that truth is valuable, spoke up against him, time and again in many different forums. Sen. Watkins powerfully opposed communism. Later historians found any truth in McCarthy’s claims against the State Department and other government agencies, and his critics, got there accidentally, below the usual levels of coincidence.

3. The sources that verify the new interpretation of history are obscure; if they involve a famous person, the sources are not those usually relied on by historians.

Most internet hoaxes simply don’t list sources. Bogus quotes circulating that have been attributed to Madison, Jefferson, Washington, Lincoln, and others, often list a year, and nothing else. When I staffed the Senate, several times a year I’d get letters to work on with claims that the Supreme Court had ruled in 1892 that the U.S. is, officially, a “Christian nation.” Usually there there was no case name attached, but I came to understand that the case referred to was the Church of the Holy Trinity vs. U.S. 1892 was far enough back that it was a difficult case for people outside of a decent law library to get — and then, it is couched in 1892 legalese, which makes it difficult to understand. It is an obscure enough case that most of the time it won’t be checked out. If the case can be produced, rarely will it be among lawyers who can interpret what happened from the fog of the language of the decision. The case is not listed at the Cornell University Law School’s on-line Legal Information Institute, nor at Findlaw.com — the databases they rely on go back to 1893. There is a full text copy at the Justicia website. [This was written in 2007.]

The case involved a law that prohibited the importing of laborers, and the Court ruled that the law probably was not intended to apply to a white, white collar worker, a preacher from England (the law was probably aimed at Chinese workers, coming as it did in that time when immigration from China was prohibited). It appears from the case that the church had argued some First Amendment justification to be exempt, and the U.S. Solicitor General had argued in response that the First Amendment requires the courts to assume that the government is hostile to religion; Justice David Brewer wrote at length about how the nation had accommodated religion over the years, especially Christianity, in dismissing the Solicitor General’s argument (he did not accept the church’s argument, either). This sort of writing is called obiter dicta in legal studies — words of an opinion wholly unnecessary to the decision. The case is cited rarely, and never for its religious “ruling,” because that was not what was ruled, and the language was not applied as law then, nor has it been since. The Supreme Court ruled that importing preachers from England was not covered by the law. The ruling makes no mention of religion.

A bit of reflection on what really happened in history should make this clear: Consider the effect of such a ruling by the Supreme Court on later cases involving textbooks, busing of parochial students, student prayer, Bible readings, etc. Had such a precedent existed, lawyers would have sniffed it out regardless its obscurity.

4. Evidence for the history is anecdotal.

America’s founders carefully wrote laws that assure religious freedom, largely by creating a separation of state and church. To those unhappy with such a separation, every utterance of a founder in which God is praised, or invoked in any way, becomes “proof” that the founders did not mean what they wrote in the laws. Anecdote trumps any other evidence, to these people.

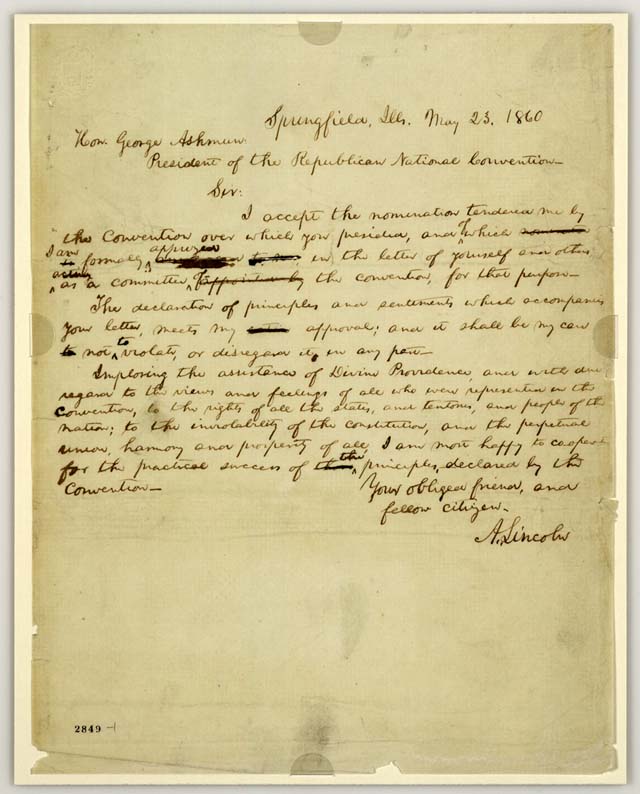

Abraham Lincoln’s letter to the president of the Republican National Convention of 1860, accepting the convention’s nomination for the presidency. It was written, you will note, from Springfield, Illinois, 200 miles away from Chicago where the convention was held.

To prove to me the piety of Abraham Lincoln, a fellow showed me photograph of a plaque on a church in Chicago, said to be the church where Abraham Lincoln said his prayers every morning during the Republican Convention of 1860, at which Lincoln got the nomination for president. Other records — newspapers, Lincoln’s letters and other documents, show that, as was the fashion in 1860, Lincoln did not attend the convention in Chicago, but as a candidate for president, stayed at home in Springfield, nearly 200 miles away.

Most real history can be read in documents, and does not need to rely on folk retellings exclusively.

5. The author says a belief is credible because it has endured for some time, or because many people believe it to be true.

Faced with the evidence that a dozen quotes he had attributed to figures such as James Madison, George Washington and Patrick Henry were whole cloth inventions, Texas quote-purveyor David Barton issued a statement urging people not to rely on them because they were “questionable.“

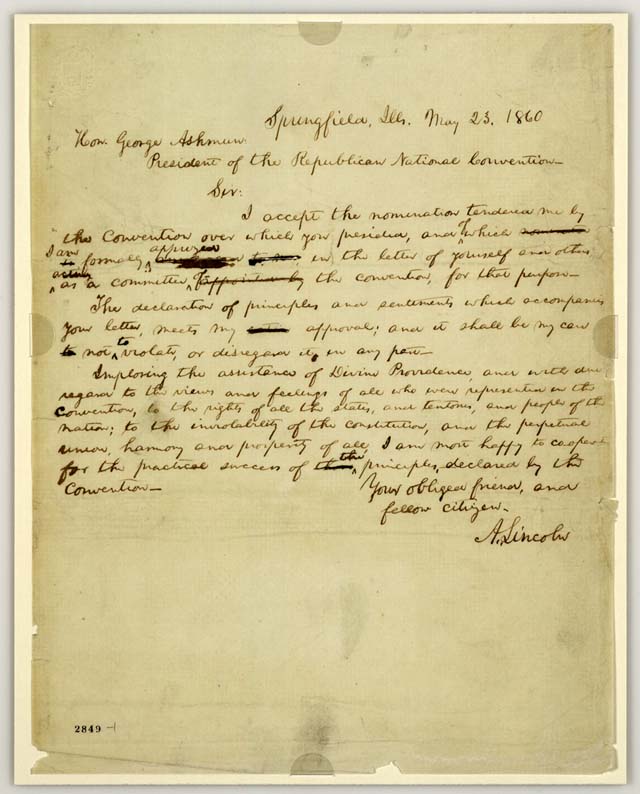

A great example of belief triumphing over fact presents itself as the Cardiff Giant, now on display at the Farmers’ Museum in Cooperstown, New York (go visit when you visit the Baseball Hall of Fame). After an argument with a cleric over whether the Bible’s claim that giants once existed, a tobacconist named George Hull hired stonecarvers to carve a giant; then he hired a farmer to bury the carving on his farm, and claim to have struck it when planting. Once discovered the “petrified man” was put on display, for a fee. Hull got lucky: Syracuse businessmen offered to buy it from him for an enormous sum.

Paleontologist Othniel Marsh inspected it on display, and pronounced it a hoax. For some odd reason, that increased the popularity of the attraction. Carnival and side show entrepreneur P. T. Barnum offered $60,000 for the carving, but was refused. Barnum then had a plaster replica made and put on display. The owners of the original hoaxed carving sued, but the suit was thrown out because they could not demonstrate the “genuineness” of their own hoax. Barnum made more money than the original. A hoaxed hoax is even more popular than the truth.

A photo (staged?) of the 1869 unearthing of the Cardiff Giant (Cardiff, New York). Photograph courtesy Farmers Museum (where the carving now rests, on display to museum visitors) via Associated Press, and via National Geographic.

6. The author has worked in isolation.

Historians often help each other. Good historians put out queries to many sources, the better to assure accuracy. So, conversely, if there are only a few people who know anything about an account, that fact alone may cause suspicion. Clifford Irving’s hoax biography of Howard Hughes, while remarkably accurate in some regards, was unraveled when enough people familiar with Hughes called the bluff — including, of course, Hughes himself. The book got as far as it did with extreme secrecy on Irving’s part. Working alone makes error easier, and is essential for intentional frauds.

7. The author must propose a new interpretation of history to explain an observation.

Various conspiracy claims require that key people act counter to their known character. If Franklin Roosevelt had “allowed” Pearl Harbor to occur in order to get the U.S. into war, his actions over the previous six years to support Britain start to make little sense. Had Lyndon Johnson been part of a conspiracy to assassinate John Kennedy, his later carrying out the legislative plan of Kennedy runs contrary to all such motivations. If the founders of the U.S. actually intended to make Christianity the state religion, their efforts to disestablish the churches in all 13 colonies, efforts to write bills of rights for each state including freedom of religion, and efforts to create the First Amendment in the Bill of Rights seem like incredible, repeated errors.

Bogus history is much like the conjectured problems that result from time travel: Change one jot of history, and there is a cascading effect on later events. In many cases,were the bogus histories accurate, what follows could not be so, and we wouldn’t be here to discuss it.

Those are the seven warning signs of bogus history. Bogus, or voodoo history should be suspected if two or more of the signs are present — though it is quite possible for actual history to show more than two signs (perhaps actual history could show all seven signs — but I’d have to see an example before stating it’s so).

More:

Spread the word; friends don't allow friends to repeat history.

Posted by Ed Darrell

Posted by Ed Darrell