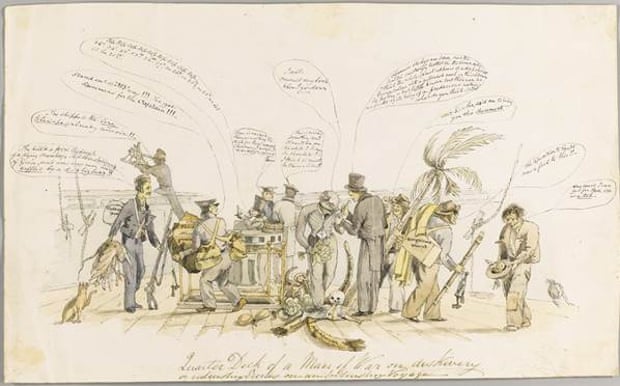

The watercolour, painted while the Beagle was anchored off the Patagonian coast in 1832, around September 24, shows fossils and botanical specimens being hauled aboard for examination by Darwin, who commands the centre of the painting in top hat and tails. The event followed Darwin’s trip ashore at Bahia Blanca, Brazil. Painting is by by Augustus Earle, who was hired as shipboard artist by Capt. FitzRoy in October 1831, but had to quit the ship soon after this painting, due to ill health. From The Guardian.

No, Darwin was not racist.

I know many Darwin students, and science students, usually concede that Darwin was “racist by today’s standards,” but better than most of his pre-Victorian and Victorian colleagues. I think that’s an unnecessary and very much inaccurate concession. Darwin simply was not racist.

To come to that conclusion, one needs to read a bunch of Darwin’s writings, and see what he really said. Darwin was bound by English usage mostly in the first half of the 19th century, and that produces confusion among people who assume “savage” is a pejorative term, and not simply the pre-1860 version of “wild” or “aboriginal.”

But beyond that, a look at Darwin’s life should produce an appreciation of the remarkable lack of bias he shows to people of color — though he does demonstrate bias against French, Germans and Turks, and it’s difficult to understand if he’s being sarcastic in those uses.

We discussed this issue way back in 2007, at Dr. P. Z. Myers’s blog, Pharyngula, back when it was a part of a series of science blogs hosted by Seed Magazine, which has gone defunct. P. Z. took an answer I gave in one post, and made a freestanding post out of it.

I was surprised, but happy to bump into the answer recently — because it remains a good summary response. It would have benefited from links, but in 2007 I wasn’t adept at adding links in other blogs (didn’t even have this one), and links were limited, as I recall.

So I’ll add in links below.

Here’s my 2007 answer to the retort, “Darwin was racist,” with no editing, but links added.

Here’s the post from P. Z. Myers, featuring my answer.

Since Ed Darrell made such a comprehensive comment on the question of whether Darwin was as wicked a racist as the illiterate ideologues of Uncommon Descent would like you to believe, I’m just copying his list here.

Remember the famous quarrel between Capt. FitzRoy and Darwin aboard the Beagle? After leaving Brazil, in their mess discussions (remember: Darwin was along to talk to FitzRoy at meals, to keep FitzRoy from going insane as his predecessor had), Darwin noted the inherent injustice of slavery. Darwin argued it was racist and unjust, and therefore unholy. FitzRoy loudly argued slavery was justified, and racism was justified, by the scriptures. It was a nasty argument, and Darwin was banned to mess with the crew with instructions to get off the boat at the next convenient stop. FitzRoy came to his senses after a few days of dining alone. Two things about this episode: First, it shows Darwin as a committed anti-racist; second, it contrasts Darwin’s views with the common, scripture-inspired view of the day, which was racist.

Darwin’s remarks about people of color were remarkably unracist for his day. We should always note his great friend from college days, the African man, [freed slave John Edmonstone,] who taught him taxidermy. We must make note of Darwin’s befriending the Fuegan,

JeremyJemmy Button [real name, Orundellico], whom the expedition was returning to his home. Non-racist descriptions abound in context, but this is a favorite area for anti-Darwinists to quote mine. Also, point to Voyage of the Beagle, which is available on line. In it Darwin compares the intellect of the Brazilian slaves with Europeans, and notes that the slaves are mentally and tactically as capable as the greatest of the Roman generals. Hard evidence of fairness on Darwin’s part.Darwin’s correspondence, especially from the voyage, indicates his strong support for ending slavery, because slavery was unjust and racist. He is unequivocal on the point. Moreover, many in Darwin’s family agreed, and the Wedgwood family fortune was put behind the movement to end slavery. Money talks louder than creationists in this case, I think. Ironic, Darwin supports the Wilberforce family’s work against slavery, and Samuel Wilberforce betrays the support. It reminds me of Pasteur, who said nasty things about Darwin; but when the chips were down and Pasteur’s position and reputation were on the line, Darwin defended Pasteur. Darwin was a great man in many ways.

Watch for the notorious quote mining of Emma’s remark that Charles was “a bigot.” It’s true, she said it. Emma said Charles was a bigot, but in respect to Darwin’s hatred of spiritualists and seances. Darwin’s brother, Erasmus, was suckered in by spiritualists. Darwin was, indeed, a bigot against such hoaxes. It’s recounted in Desmond and Moore’s biography, but shameless quote miners hope their audience hasn’t read the book and won’t. Down here in Texas, a lot of the quote miners are Baptists. I enjoy asking them if they do not share Darwin’s bigotry against fortune tellers. Smart ones smile, and drop the argument.

One might hope that the “Darwin-was-racist” crap comes around to the old canard that Darwin’s work was the basis of the campaign to kill the natives of Tasmania. That was truly a terrible, racist campaign, and largely successful. Of course, historians note that the war against Tasmanians was begun in 1805, and essentially completed by 1831, when just a handful of Tasmanians remained alive. These dates are significant, of course, because they show the war started four years prior to Darwin’s birth, and it was over when Darwin first encountered Tasmania on his voyage, leaving England in 1831. In fact, Darwin laments the battle. I have often found Darwin critics quoting Darwin’s words exactly, but claiming they were the words of others against Darwin’s stand.

Also, one should be familiar with Darwin’s writing about “civilized” Europeans wiping out “savages.” In the first place, “savage” in that day and in Darwin’s context simply means ‘not living in European-style cities, with tea and the occasional Mozart.’ In the second, and more critical place, Darwin advances the argument noting that (in the case of the Tasmanians, especially), the “savages” are the group that is better fit to the natural environment, and hence superior to the Europeans, evolutionarily. Darwin does not urge these conflicts, but rather, laments them. How ironic that creationist quote miners do not recognize that.

P. Z. closed off:

Isn’t it odd how the creationists are so divorced from reality that they can’t even concede that Darwin was an abolitionist, and are so reduced in their arguments against evolution that they’ve had to resort to the desperate “Darwin beats puppies!” attack?

Sadly, many of the posts in that old home for Pharyngula eroded away as the old Appalachian Mountain range eroded to be smaller than the Rockies. Time passes, even the rocks change.

Darwin’s still not racist. Creationists and other malignant forces revive the false claim, from time to time.

More:

Posted by Ed Darrell

Posted by Ed Darrell

![Viva la república! Viva el Cura Hidalgo! Una página de Gloria, TITLE TRANSLATION: Long live the republic! Long live Father Hidalgo! A page of glory. Between 1890 and 1913. Prints and Photographs Division. Reproduction Information: Reproduction Nos.: LC-USZ62-98851 (b&w film copy neg.), LC-DIG-ppmsc-04595 (digital file from original, recto), LC-DIG-ppmsc-04596 (digital file from original, verso); Call No.: PGA - Vanegas, no. 123 (C size) [P&P] Catalog Record: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppmsc.04595](https://i0.wp.com/www.loc.gov/wiseguide/sept09/images/Mexican_A_thumb.jpg)

![A street in Guanajuato, Mexico. Between 1880 and 1897. Prints and Photographs Division. Reproduction Information: Reproduction No.: LC-D418-8481 (b&w glass neg.); Call No.: LC-D418-8481 <P&P>[P&P] Catalog Record: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/det.4a27131](https://i0.wp.com/www.loc.gov/wiseguide/sept09/images/Mexican_B_thumb.jpg)