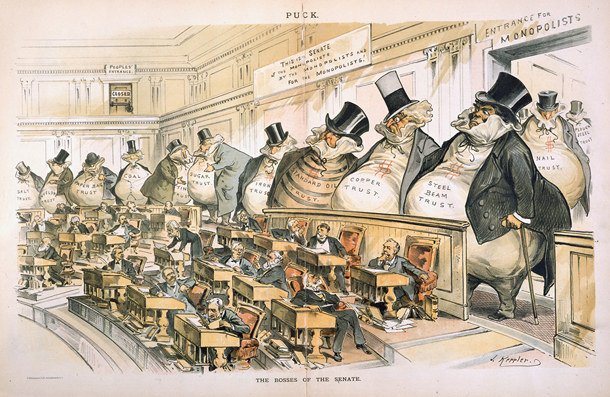

From the Historian of the U.S. Senate, a Joseph Keppler cartoon from Puck Magazine, “The Making of a Senator.” Print by J. Ottmann Lith. Co. after Joseph Keppler, Jr., Puck. Lithograph, colored, 1905-11-15. Image with text measurement Height: 18.50 inches (46.99 cm) Width: 11.50 inches (29.21 cm) Cat. no. 38.00624.001

This is a lithograph after a cartoon by Joseph Keppler in Puck Magazine, November 15, 1905. Keppler’s cartoons kept on the heat for some legislative solution to continuing corruption in state legislatures and the U.S. Senate, driven by the ability of large corporations and trusts to essentially purchase entire states’ legislatures, and tell legislators who to pick for the U.S. Senate.

Described by the Historian of the U.S. Senate:

The “people” were at the bottom of the pile when it came to electing U.S. senators, when Joseph Keppler, Jr.’s cartoon, “The Making of a Senator, ” appeared in Puck on November 15, 1905. Voters elected the state legislatures, which in turn elected senators. Keppler depicted two more tiers between state legislatures and senators: political bosses and corporate interests. Most notably, he drew John D. Rockefeller, Sr., head of the Standard Oil Corporation, perched on moneybags, on the left side of the “big interests. ”

This cartoon appeared while muckraking magazine writers such as Ida Tarbell and David Graham Phillips were accusing business of having corrupted American politics. The muckrakers charged senators with being financially beholden to the special interests. Reformers wanted the people to throw off the tiers between them and directly elect their senators–which was finally achieved with ratification of the 17th Amendment in 1913.

Recent scuttlebutt about repealing the 17th Amendment seems to me wholly unconnected from the history. The 17th Amendment targeted corruption in the Senate and states. It largely worked, breaking the course of money falling from rich people and large corporations into the hands of everyone but the people, and breaking the practice of corporate minions getting Senate seats, to do the bidding of corporations and trusts.

Anti-corruption work was part of the larger Progressive Agenda, which included making laws that benefited people, such as clean milk and food, pure drugs, and banking and railroad regulation so small farmers and businessmen could make a good living. Probably the single best symbol of the Progressive movement was “Fighting Bob” LaFollette, Congressman, Governor and U.S. Senator from Wisconsin. LaFollette was a great supporter of the 17th Amendment

Again from the Senate Historian:

Nicknamed “Fighting Bob,” La Follette continued to champion Progressive causes during a Senate career extending from 1906 until his death in 1925. He strongly supported the 17th Amendment, which provided for the direct election of senators, as well as domestic measures advocated by President Woodrow Wilson’s administration, including federal railroad regulation and laws protecting workers rights. La Follette worked to generate wider public accountability for the Senate. He advocated more frequent and better publicized roll call votes and the publication of information about campaign expenditures.

Criticism of the 17th Amendment runs aground when it analyzes the amendment by itself, without reference to the democracy- and transparency-increasing components from the rest of the Progressive movements’ legislative actions from 1890 to 1930.

No one favors corruption and damaging secrecy in politics. By pulling the 17th out of context, critics hope to persuade Americans to turn back the clock to more corrupt times.

More:

- See Keppler’s 1889 cartoon on the same topic, a more famous cartoon

- History of the 17th Amendment at National Archives and Records Administration’s (NARA) OurDocuments.gov

- For elementary students (and, conservatives, perhaps), an explanation of the amendment at Kids.Laws.Com

- “States’ Wrongs – Conservatives’ illogical, inconsistent effort to repeal the 17th Amendment,” David Schleiche, Slate.com, February 2014

Save

Posted by Ed Darrell

Posted by Ed Darrell