Photos of Frank and Virginia Hewlett, and Frank’s reporting colleague William McDougall, in post-war life. Images found at The Downhold Project.

Frank Hewlett told me all about Washington, D.C. In my youth, in the potato fields of southern Idaho, and on the slopes of the towering Wasatch Front in Utah, Frank Hewlett came on the pages of the Salt Lake Tribune nearly every day, telling what happened in Washington and how that might affect us in the west.

Two doors north of our home on Conant Avenue in Burley was the home of Henry C. Dworshak. Though we rarely saw him at home, Dworshak’s work in Washington as U.S. Senator was detailed by Hewlett. (Irony never far away, when my older brother Wes won a competitive appointment to the U.S. Air Force Academy from Dworshak, the first they met was to pose for a picture for the local newspaper.)

Frank Hewlett told me, and a half-million other people, about the ins and outs of getting authorization and funding to build massive dams on the Colorado River, at Flaming Gorge, Utah, and at Glen Canyon.

In 1979 I moved to Washington, D.C., doing press work for a Utah senator. First full day on the job, who strides into the office but Frank Hewlett.

I got there late in Frank’s career. He was nearing retirement, and he was battling cancer. His wife, Virginia, still suffered from the effects of imprisonment in the Philippines by Japanese forces in the World War II. Editors at the Tribune seemed to want to push him out of the job. That didn’t seem to phase him much. He’d seen much worse.

Hewlett reported for UPI during World War II — UPI’s glory days, the same agency from which Edward R. Murrow hired some of his best reporters in London (including Walter Cronkite). Frank had been a personal friend of Gen. Douglas MacArthur, close enough that when the U.S. got back to Manila and pushed the Japanese out, MacArthur loaned Frank his personal jeep, so Frank could drive around to the Japanese prison camps to try to find his wife, who’d been captured because she stayed behind to burn the U.S. flag from the embassy, when the Japanese invaded. Hewlett found Virginia, weighing way under 100 pounds and needing years of loving care to get back to a semblance of the beautiful young bride the war stole from Frank.

As with every other veteran of World War II I ever knew, Frank Hewlett didn’t talk about the war much. Once over lunch, he told me I could go look up his reports, but he wasn’t going to rehash them.

You might wonder why I fondly recall a guy who could be so curt and acerbic, who wouldn’t tell me the stories I wanted to hear from him about the war. There were other tales he was happy to talk about — from where comes the old political saw, “You can’t go back to Pocatello,” how Republicans and Democrats combined to make National Parks and great Bureau of Reclamation dams, how Dwight Eisenhower was so concerned about snow and cold messing up John Kennedy’s inauguration that he ordered troops with flamethrowers out in the early morning to melt the ice and dry the streets of Washington. Great history, great stories.

Didn’t hurt when he learned I had lived in Burley, Idaho. Two refugees from the spud fields, together in D.C.

When I made a goof in a press release, when our legislation ran into problems, Frank wouldn’t barge into the office and head to the coffee pot. He’d poke his head through door, say, “Can I buy you a coffee?” Then in one of the Senate eateries he’d quietly tell me how he’d fix whatever problem I was having. Most often he had good advice, but always he had great concern that the youngest press guy in the Senate get through the trouble.

Once I mentioned how “fighting the bastards” reminded me of war, and he corrected me: Organizational conflict is nothing like war, and the bastards, well, often they are the good guys. He said he’d written a poem about that. He was sure he had a copy, and he’d get it to me. He couldn’t remember all the lines, he said — but he gave me a recitation of what he said he could remember: “The Battling Bastards of Bataan . . . No one gives a damn.” He explained that soldiers at Bataan despaired that no one knew their faite

Virginia grew ill. Cancer eventually took her. Kathryn and I visited Frank at his Virginia home, intending to take him out to dinner. His own cancer and other ills bothered him, he didn’t want to go out — we ended up eating hot dogs he had in the refrigerator. Frank reminded me he’d get me a copy of his poem.

Didn’t happen. At his funeral at that little Catholic Church in Alexandria, the eulogist told about Frank’s love for Virginia and how it survived the war, and said he’d been a correspondent in a lot of tight places.

Today, I found a website with poems about World War II, and in a quick scroll found Frank’s name.

We’re the battling bastards of Bataan;

No mama, no papa, no Uncle Sam.

No aunts, no uncles, no cousins, no nieces,

No pills, no planes, no artillery pieces

And nobody gives a damn

Nobody gives a damn.

by Frank Hewlett 1942

Now I have a copy of Frank’s poem.

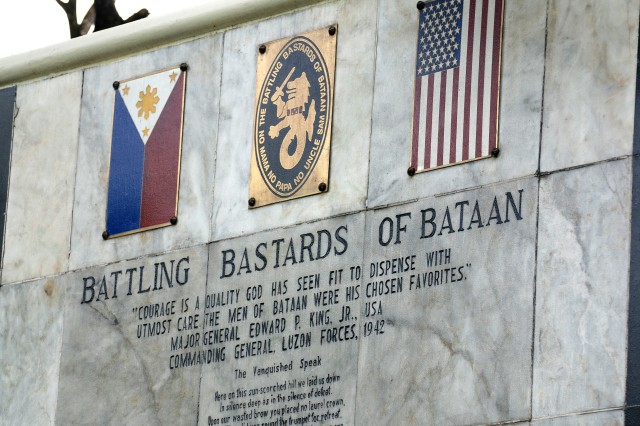

From Army.mil, the U.S. Army’s home page: Photo Credit: Rachael Tolliver/ The names and units of those U.S. military personal who died at, or in route to the Capas Concentration Camp during the Bataan Death March, are etched on marble and titled “Battling Bastards of Bataan.” The memorial is located at the Capas National Shrine, in Capas, Tarlac, Philippines. “Battling Bastards of Bataan” was a limerick poem penned by Frank Hewlett, Manila bureau chief for UP and the last reporter to leave Corregidor before it fell to the Japanese. “We’re the battling bastards of Bataan/No mama, no papa, no Uncle Sam/No aunts, no uncles, no cousins, no nieces/No pills, no planes, no artillery pieces/And nobody gives a damn.”

More:

- Hartford (Connecticut) Courant story on the April 2012 ceremony marking the 70th anniversary of the Bataan Death March, with mention of Hewlett’s poem

- “A War Correspondent’s Story,” about Frank Hewlett and Bill McDougall, a story by fellow UP reporter Bill Ryan, at The Downhold Project

- Greg’s Running Adventures, post on a run to honor the New Mexico National Guard victims and survivors of the Bataan Death March, at White Sands, New Mexico, March 2013

- Charlton Ogburn, historian of Merrill’s Marauders, and organizational wisdom

Posted by Ed Darrell

Posted by Ed Darrell