How many ways can we say happy birthday to a great scientist born on Pi Day? So, an encore post.

E=energy; m=mass; c=speed of light

Happy Einstein Day! to us. Albert’s been dead since 1955 — sadly for us. Our celebrations now are more for our own satisfaction and curiosity, and to honor the great man — he’s beyond caring.

Almost fitting that he was born on π Day, no? I mean, is there an E=mc² Day? He’s 138 years old today, and famous around the world for stuff that most people still don’t understand.

Fittingly, perhaps, March 14 now is celebrated as Pi Day, in honor of that almost magical number, Pi, used to calculate the circumference of a circle. Pi is 3. 1415~, and so the American date 3/14 got tagged as Pi Day.

Albert Einstein was born on March 14, 1879, in Ulm, Germany, to Hermann and Pauline Einstein.

26 years later, three days after his birthday, he sent off the paper on the photo-electric effect; that paper would win him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921.

In that same year of 1905, he published three other papers, solving the mystery of Brownian motion, describing what became known as the Special Theory of Relativity and solving the mystery of why measurements of the light did not show any effects of motion as Maxwell had predicted, and a final paper that noted a particle emitting light energy loses mass. This final paper amused Einstein because it seemed so ludicrous in its logical extension that energy and matter are really the same stuff at some fundamental point, as expressed in the equation demonstrating an enormous amount of energy stored in atoms, E=mc².

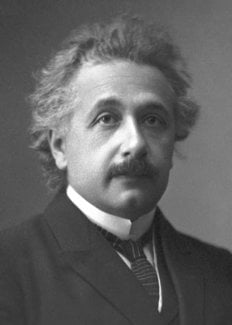

Albert Einstein as a younger man – Nobel Foundation image

Any one of the papers would have been a career-capper for any physicist. Einstein dashed them all off in just a few months, forever changing the fields of physics. And, you noticed: Einstein did not win a Nobel for the Special Theory of Relativity, nor for E=mc². He won it for the photo-electric effect. Irony in history. Nobel committee members didn’t understand Einstein’s other work much better than the rest of us today.

117 years later, Einstein’s work affects us every day. Relativity theory at some level I don’t fully understand makes possible the use Global Positioning Systems (GPS), which revolutionized navigation and mundane things like land surveying and microwave dish placement.

Development of nuclear power both gives us hope for an energy-rich future, and gives us fear of nuclear war. Sometimes, even the hope of the energy rich future gives us fear, as we watch and hope nuclear engineers can control the piles in nuclear power plants damaged by earthquakes and tsunami in Japan.

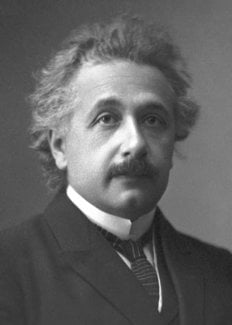

Albert Einstein on a 1966 US stamp (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

If Albert Einstein was a genius at physics, he was more dedicated to pacifism. He resigned his German citizenship to avoid military conscription. His pacifism made the German Nazis nervous; Einstein fled Germany in the 1930s, eventually settling in the United States. In the U.S., he was persuaded by Leo Szilard to write to President Franklin Roosevelt to suggest the U.S. start a program to develop an atomic weapon, because Germany most certainly was doing exactly that. But while urging FDR to keep up with the Germans, Einstein refused to participate in the program himself, sticking to his pacifist views. Others could, and would, design and build atomic bombs. (Maybe it’s a virus among nuclear physicists — several of those working on the Manhattan Project were pacifists, and had great difficulty reconciling the idea that the weapon they worked on to beat Germany, was deployed on Japan, which did not have a nuclear weapons program.)

Everybody wanted to claim, and honor Einstein; USSR issued this stamp dedicated to Albert Einstein Русский: Почтовая марка СССР, посвящённая Альберту Эйнштейну (Photo credit: HipStamp)

Einstein was a not-great father, and probably not a terribly faithful husband at first — though he did think to give his first wife, in the divorce settlement, a share of a Nobel Prize should he win it. Einstein was a good violinist, a competent sailor, an incompetent dresser, and a great character.

His sister suffered a paralyzing stroke. For many months Albert spent hours a day reading to her the newspapers and books of the day, convinced that though mute and appearing unconscious, she would benefit from hearing the words. He said he did not hold to orthodox religions, but could there be a greater show of faith in human spirit?

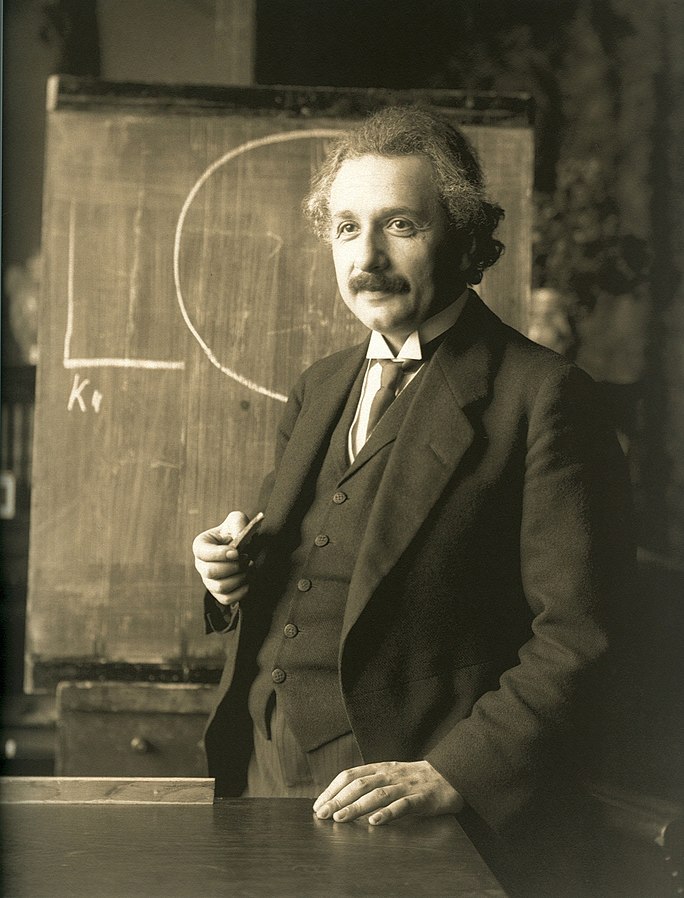

Einstein in 1950, five years before his death

When people hear clever sayings, but forget to whom the bon mots should be attributed, Einstein is one of about five candidates to whom all sorts of things are attributed, though he never said them. (Others include Lincoln, Jefferson, Mark Twain and Will Rogers). Einstein is the only scientist in that group. So, for example, we can be quite sure Einstein never claimed that compound interest was the best idea of the 20th century. This phenomenon is symbolic of the high regard people have for the man, even though so few understand what his work was, or meant.

A most interesting man. A most important body of work. He deserves more study and regard than he gets, in history, diplomacy and science.

Does anyone know? What was Albert Einstein’s favorite pie?

More, Resources:

- American Institute of Physics (AIP) on-line exhibit on the life and work of Einstein — good stuff!

- Einstein’s biography at the Nobel Foundation website

- NPR’s Talk of the Nation show on Einstein’s birthday in 2005, featuring New York Times science correspondent Dennis Overbye, author of Einstein in Love

- Effect Measure at SciBlogs had a nice tribute today

- History Channel’s series, 10 Days that Unexpectedly Changed America featured a film on the letter Einstein wrote to FDR, “Einstein’s Letter.” Here’s a teachers guide

- The National Museum of Nuclear Science and History in Albuquerque will hold its 15th Annual Einstein Gala Dinner on March 17, at the Hotel Albuquerque; “Dr. Lisa Randall has been named the recipient of the 2012 National Award of Nuclear Science and History, which is presented annually by National Atomic Museum Foundation to a prominent person that has had an impact on nuclear issues.”

- How Einstein Proved the Size and Existence of Atoms [Video] (gizmodo.com)

- 11 Unserious Photos of Albert Einstein (mentalfloss.com)

- Happy Birthday Einstein (nextbigwhat.com)

- Einstein > π (mathjokes4mathyfolks.wordpress.com)

- Celebrating Einstein’s birthday on Pi Day (sciencelens.wordpress.com)

- Of course, there is Einstein on the Beach, “an opera in four acts (framed and connected by five ‘knee plays’ or intermezzos), scored by Philip Glass and directed by theatrical producer Robert Wilson.”

- 15 quotes from Einstein, on his birthday, from the Christian Science Monitor (these should be accurate, if we go by the reputation of this venerable old paper-gone-electric; however, the feature does NOT include citations . . . see any problems?

- New York Times article on Einstein’s death, April 18, 1955 (the paper is from April 19)

- HuffPo list of 10 facts about Einstein; accurate?

- Einstein’s desk and office in Princeton, New Jersey (no typewriter; can you find a telephone?)

- Quote of the moment: Einstein on nature’s secrecy

Spread the word; friends don't allow friends to repeat history.

Posted by Ed Darrell

Posted by Ed Darrell