Before I was a teacher, I led a tough band of people at the Department of Education, and I plied corporate America (among other jobs). I spent a couple of years in American Airlines‘s corporate change project, facilitating leadership courses for more than 10,000 leaders in the company, as one of a team of about 20 inside consultants. I had a fine time in management consulting with Ernst & Young LLP (now EY).

W. Edwards Deming, Wikipedia image

Back then “quality” was a watchword. Tom Peters’s and Robert H. Waterman, Jr.‘s book, In Search of Excellence, showed up in everybody’s briefcase. If your company wasn’t working with Phillip Crosby (Quality is Free), you were working with Joseph Juran, or the master himself, W. Edwards Deming. If your business was highly technical, you learned more mathematics and statistics that you’d hoped never to have to use so you could understand what Six Sigma meant, and figure out how to get there.

Joseph Juran. Another exemplar of the mode of leadership that takes lawyers out of law, putting them to good work in fields not thought to be related.

For a few organizations, those were heady times. Management and leadership research of the previous 50 years seemed finally to have valid applications that gave hope for a sea change in leadership in corporations and other organizations. In graduate school I’d been fascinated and encouraged by the work of Chris Argyris and Douglas McGregor. “Theory X and Theory Y” came alive for me (I’m much more a Theory Y person).

Deming’s 14 Points could be a harsh checklist, harsh master to march to, but with the promise of great results down the line.

A lot of the work to get high quality, high performance organizations depended on recruiting the best work from each individual. Doing that — that is, leading people instead of bossing them around — was and is one of the toughest corners to turn. Tough management isn’t always intuitive.

For the salient example here, Deming’s tough statistical work panics workers who think they will be held accountable for minor errors not their doing. In a traditional organization, errors get people fired.

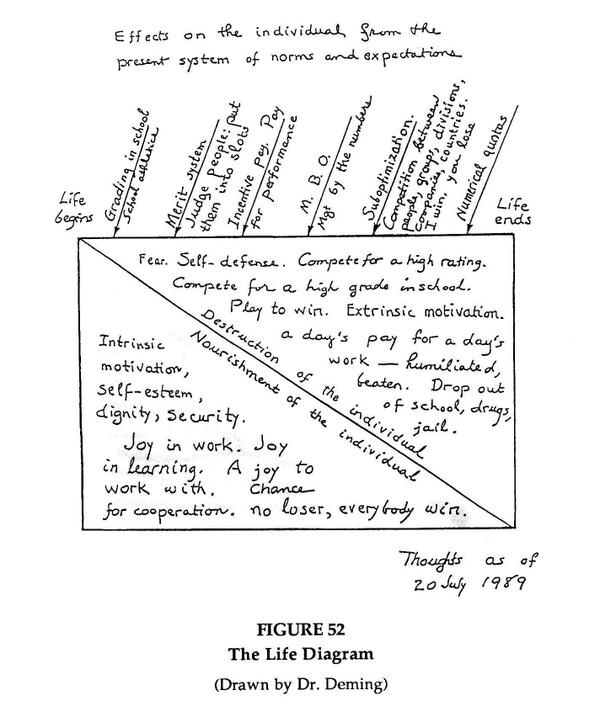

Deming’s frequent point was that errors are not the worker’s doing, but instead are caused by managers, or by managerial failure to support the worker in getting quality work. In any case, Deming comes down hard against firing people to try to get quality. One of his 14 points is, “Drive out fear.” In his seminars and speeches, that point was explained with, among other things, a drive to do away with annual performance reviews (wow, did that cause angst and cognitive dissonance at Ernst & Young!). Performance reviews rarely touch on what a person needs to do to create quality, and generally the review session becomes a nit-picking exercise that leaves ratees angry, and less capable and willing to do quality work. So Deming was against them as usually practiced.

Fast forward to today.

American schools are under fire — much of that fire unjustified, but that’s just one problem to be solved. Evaluations of teachers is a big deal because many people believe that they can fire their way to good schools. ‘Just fire the bad teachers, and the good ones will pull things out.’

Yes, that’s muddled thinking, and contrary to the requirements of the No Child Left Behind Act, there is no research to support the general idea, let alone specific applications.

Education leaders are trained in pedagogy, and not in management skills, most often — especially not in people leadership skills. Teacher evaluations? Oh, good lord, are they terrible.

Business adviser and healer, Tom Peters (from his website, photo by Allison Shirreffs)

In some search or other today I skimmed over to Tom Peters’s blog — and found this short essay, below. Every school principal in America should take the three minutes required to read it — it will be a solid investment.

dispatches from the new world of work

Deming & Me

W. Edwards Deming, the quality guru-of-gurus, called the standard evaluation process the worst of management de-motivators. I don’t disagree. For some reason or other, I launched several tweets on the subject a couple of days ago. Here are a few of them:

- Do football coaches or theater directors use a standard evaluation form to assess their players/actors? Stupid question, eh?

- Does the CEO use a standard evaluation form for her VPs? If not, then why use one for front line employees?

- Evaluating someone is a conversation/several conversations/a dialogue/ongoing, not filling out a form once every 6 months or year.

- If you (boss/leader) are not exhausted after an evaluation conversation, then it wasn’t a serious conversation.

- I am not keen on formal high-potential employee I.D. programs. As manager, I will treat all team members as potential “high potentials.”

- Each of my eight “direct reports” has an utterly unique professional trajectory. How could a standardized evaluation form serve any useful purpose?

- Standardized evaluation forms are as stupid for assessing the 10 baristas at a Starbucks shop as for assessing Starbucks’ 10 senior vice presidents.

- Evaluation: No problem with a shared checklist to guide part of the conversation. But the “off list” discussion will by far be the most important element.

- How do you “identify” “high potentials”? You don’t! They identify themselves—that’s the whole point.

- “High potentials” will take care of themselves. The great productivity “secret” is improving the performance of the 60% in the middle of the distribution.

Tom Peters posted this on 10/09/13.

I doubt that any teacher in a public elementary or secondary school will recognize teacher evaluations in that piece.

And that, my friends, is just the tip of the problem iceberg.

An enormous chasm separates our school managers in this nation from good management theory, training and practice. Walk into almost any meeting of school administrators, talk about Deming, Juran, Crosby, and you’re introducing a new topic (not oddly, Stephen Covey’s book, 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, sits on the shelf of many principals — probably unread, but certainly unpracticed).

Texas works to make one standardized evaluation form for every teacher in every grade, in every subject, in every school. Do you see anything in Peters’s advice to recommend that? In many systems, teachers may choose whether evaluators will make surprise visits to the classroom, or only scheduled visits. In either case, visits are limited, generally fewer than a dozen visits get made to a teacher’s classroom in a year. The forms get filled out every three months, or six weeks. Take each of Tom’s aphorisms, it will be contrary to the way teacher evaluations usually run.

Principals, superintendents, you don’t have to take this as gospel. It’s only great advice from a guy who charges tens of thousands of dollars to the greatest corporate leaders in the world, to tell them the same thing.

It’s not like you want to create a high-performing organization in your school, is it?

More:

Spread the word; friends don't allow friends to repeat history.

Posted by Ed Darrell

Posted by Ed Darrell