More misquoting of “the Founders”:

For America’s poster featuring a quote falsely claimed to be from Patrick Henry. The racial right wingers won’t tell you, but the painting is a portrait by George Bagby Matthews c. 1891, after an original by Thomas Sully.

It’s baseball season. I love a pitch into the wheelhouse.

The radical right-wing political group For America — a sort of latter-day Redneck Panther group — invented this one, and pasted it up on their Facebook site this morning.

You know where this is going, of course. Patrick Henry didn’t say that. The poster is a hoax.

Your Hemingway [Excrement] Detector probably clanged as soon as you pulled the poster up. Patrick Henry was a powerful opponent to the Constitution.

Opposed to the Constitution? Oh, yes. It helps to know a bit of history.

Henry was at best suspicious of the drive to get a working, central government after the Treaty of Paris ended the American Revolution. While George Washington needed an interstate authority, at least to resolve disputes between the states, in order to create a commercial entity to build a path into the Ohio Valley, Henry was opposed. To be sure, Washington was scheming a bit, with his dreaming: Washington held title to more than 15,000 acres of land in the Ohio Valley, his fee for having surveyed the land for Lord Fairfax many years earlier. Washington stood to get wealthy from the sale of the land — if a path into and out of the Ohio could be devised. Washington struggled for years to get a canal through — seen today in the remains of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal from Washington, D.C., up along the Potomac River.

Henry was so opposed to the states’ working together that he refused to notify Virginia’s commissioners appointed to a commission to settle the fishing and title dispute to the Chesapeake Bay, between Maryland and Virginia especially, and including Delaware. When Maryland’s commissioners showed up in Fairfax for the first round of negotiations, they could not find the Virginia commissioners at all. So they called on Gen. Washington at his Mt. Vernon estate (as about a thousand people a year did in those years). Washington recognized immediately how this collaboration could aid getting a path through Maryland to the Ohio.

Perplexed at the abject failure of Virginia’s government, Washington dispatched messages to the Virginia commissioners, including a young man Washington did not know, James Madison. Washington was shocked and disappointed to learn the Virginians did not know they had been appointed. He suggested the Marylanders return home, and immediately began working with Madison to make the commission work. When this group settled the Chesapeake Bay boundaries and fishing issues, and Washington’s war aide Alexander Hamilton was entangled in a separate but similar dispute between New York and New Jersey over New York Harbor, Washington introduced Hamilton and Madison to each other, and suggested they broaden their work. Ultimately this effort produced the Annapolis Convention among five colonies, which called for a convention to amend the Articles of Confederation. The Second Continental Congress agreed to the proposal.

When the delegates met at Philadelphia, they determined the Articles of Confederation irreparably flawed. Instead, they wrote what we now know as the Constitution.

Patrick Henry opposed each step. Appointed delegate to the Philadelphia Convention in 1787, he refused to serve. Instead, he was elected Governor of Virginia, and proceeded to organize opposition to ratification of the Constitution. Madison’s unique ratification process, sending the Constitution to conventions of the people in each state, instead of to the state legislatures, was designed to get around Henry’s having locked up opposition to ratification in the Virginia Assembly.

Henry led opposition to ratification at the Virginia convention. Outflanked by Madison, Henry was enraged by Virginia’s ratification. Virginia had called for the addition of a bill of rights to the document, and the ratification campaign was carried partly on Madison’s promise that he would propose a bill of rights as amendments, as soon as the new federal government got up and running. Henry sought to thwart Madison, blocking Madison’s appointment as U.S. senator, in the state legislature. When Madison fell back to run for the House of Representatives, Henry found the best candidate to oppose Madison in the Tidewater area and threw all his support behind that candidate. (James Monroe was that candidate; in one of the more fitting ironies of history, during the campaign Monroe was persuaded to Madison’s side; Madison won the election, and the lifelong friendship and help of Monroe.)

When the new federal government organized, Henry refused George Washington’s invitation to join it in any capacity. Henry continued to oppose the Constitution and its government to his death.

Consequently, it is extremely unlikely Henry would have ever suggested that the Constitution was a useful tool in any way, especially as a defense of freedom; Henry saw the Constitution as a threat to freedom.

There are good records of some of the things Henry really did say about the Constitution. Henry regarded the Constitution as tyranny, and said exactly that in his speech against the Constitution on June 5, 1788:

It is said eight states have adopted this plan. I declare that if twelve states and a half had adopted it, I would, with manly firmness, and in spite of an erring world, reject it. You are not to inquire how your trade may be increased, nor how you are to become a great and powerful people, but how your liberties can be secured; for liberty ought to be the direct end of your government.

In the same speech, Henry challenged the right of the people even to consider creating a Constitution:

The assent of the people, in their collective capacity, is not necessary to the formation of a federal government. The people have no right to enter into leagues, alliances, or confederations; they are not the proper agents for this purpose. States and foreign powers are the only proper agents for this kind of government.

Probably diving into hyperbole, Henry portrayed the Constitution itself as a threat to liberty, not a protection from government:

When I thus profess myself an advocate for the liberty of the people, I shall be told I am a designing man, that I am to be a great man, that I am to be a demagogue; and many similar illiberal insinuations will be thrown out: but, sir, conscious rectitude outweighs those things with me.

I see great jeopardy in this new government. I see none from our present one. I hope some gentleman or other will bring forth, in full array, those dangers, if there be any, that we may see and touch them.

Anyone familiar with the history, with the story of Patrick Henry and the conflicting, often perpendicular story of the creation of the Constitution, would be alarmed at a quote in which Henry appears to claim the Constitution a protector of rights of citizens — it’s absolutely contrary to almost everything he ever said.

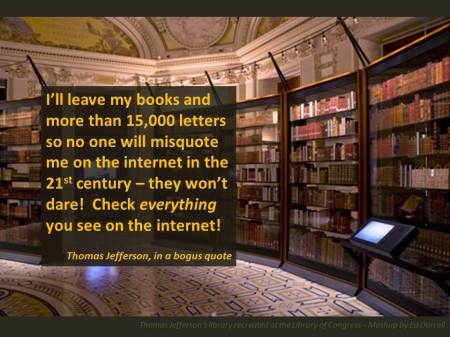

Perhaps most ironic, for our right-wing friends: The quote on the poster above was invented as a defense against abuses of the Constitution by the right. Wikiquote tracked it back to its invention:

The Constitution is not an instrument for the government to restrain the people, it is an instrument for the people to restrain the government — lest it come to dominate our lives and interests.

- As quoted in The Best Liberal Quotes Ever : Why the Left is Right (2004) by William P. Martin. Though widely attributed to Henry, this statement has not been sourced to any document before the 1990s and appears to be at odds with his beliefs as a strong opponent of the adoption of the US Constitution.

“History?” For America might say. “We don’t got no history. We don’t NEED NO STINKIN’ HISTORY!”

And so they trip merrily down the path to authoritarian dictatorship, denying their direction every step of the way to their ultimate end.

The rest of us can study history, and discover the truth.

More:

- Federalists and Anti-Federalists – What is the Difference? (hankeringforhistory.com)

- Northwest History dogged this one down earlier — wish I’d had it when I wrote the post (update April 10, 2013)

- Baylor Institute of Religion comment

- Yes, I covered this same bogus quote last year; conservatives claim not to like environmentalism, nor revisions of history, but they recycle the old prevarications with great alacrity

Spread the word; friends don't allow friends to repeat history.

Posted by Ed Darrell

Posted by Ed Darrell