Were it true that DDT is a magic solution to malaria, by all measures India should be malaria free.

Not only is India not malaria-free, but the disease increases in infections, deaths, and perhaps, in virulence.

Map showing location of Odisha, or Orissa, state, in India. Wikipedia image

Since the late 1990s a small, well-funded band of chemical and tobacco industry propagandists conducted a campaign of calumny against Rachel Carson, environmentalists in general, scientists and health care workers, claiming that an unholy and wrongly-informed conspiracy took DDT off the market just as great strides were beginning to be made against malaria.

As a consequence, this group argues, malaria infections and deaths exploded, and tens of millions of people died unnecessarily.

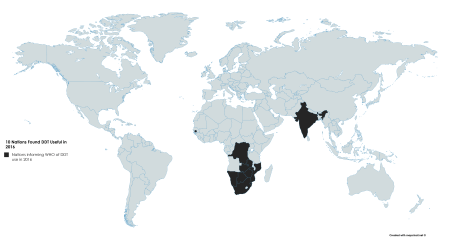

That’s a crock, to be sure. Rachel Carson’s 1962 book, Silent Spring, inspired an already-established campaign against DDT. But the malaria eradication program begun with high hopes by the World Health Organization in 1955, foundered in 1963 when the campaign turned to central, tropical Africa. Overuse of DDT in agriculture and minor pest control had bred DDT-resistant and immune mosquitoes. Malaria fighters could not knock down local populations of mosquitoes well enough to let medical care cure infected humans. (The campaign was not helped by political instability in some of the African nations; 80% of houses in an affected area need to be sprayed inside to stop malaria, and that requires government organizational skills, manpower and money that those nations could not muster.)

Detail map of Odisha state, India; map by Jayanta Nath, Wikipedia image

That was just a year after Carson’s book hit the shelves. DDT had been banned nowhere. WHO’s workers tried to get a campaign going, but complete failures stopped the program in 1965; in 1969 WHO’s board met and officially killed the malaria eradication program, in favor of control.

Malaria infections and deaths did not expand with the end of WHO’s campaign. At peak DDT use, roughly 1958 to 1963, malaria deaths are estimated by WHO to have been as high as 5 million per year, 4 million by 1963. Total malaria infections, worldwide, were 500 million.

The first bans on DDT use came in Europe. When the U.S. banned DDT use on crops in 1972, okaying use to fight malaria, malaria deaths had fallen to more than 2 million annually by optimistic estimates. Death rates and infection rates continued to fall without a formal eradication campaign. By the late 1980s, malaria killed about 1.5 million each year, a great improvement over the DDT go-go days, but still troubling.

Beating malaria is a multi-step program. Malaria parasites must complete a life cycle in a human host, and then when jumping to a mosquito, another cycle of about two weeks in the mosquito’s gut, before being transmissible back to humans. Knocking down mosquito populations helps prevent transmission temporarily, but that is only useful if in that period the human hosts can be cured of the parasites.

In the late 1980s, malaria parasites developed strong resistance and immunity to pharmaceuticals given to humans to cure them. Regardless mosquito populations, human hosts were always infected, ready to transmit the parasite to any mosquito and send drug-resistant malaria on to dozens more.

From about 1990 to about 2002, malaria deaths rose modestly to more than 1.5 million annually.

New pharmaceuticals, and new regimens of administration of pharmaceuticals, increased the effectiveness of human treatments; coupled with much better understanding of malaria vectors, the insects that transmit the disease, and geographical data and other technological advances to speed diagnosis and treatment of humans, and increase prevention measures, WHO and private foundations started a series of programs in malaria-endemic nations to reduce infections and deaths. Insecticide-impregnated bednets proved to be less-expensive and more effective than Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS) featuring DDT or any of the other 11 pesticides WHO authorizes for home spraying. (Home spraying targets mosquitoes that carry malaria, and limits expensive overuse of pesticides, plus limits and prevents environmental damage.)

Health care workers and most nations made dramatic progress in controlling and eliminating malaria, between 2000 and 2015, mostly without using DDT which proved increasingly ineffective at controlling mosquitoes, and which also proved unpopular among malaria-affected peoples whose cooperation is necessary to fight the disease.

By 2014, fewer than 220 million people got malaria infections, worldwide, a reduction of about 55% over DDT’s peak-use years. This is remarkable considering the population of the planet more than doubled in that time, and population in malaria-endemic areas rose even more. Malaria deaths were reduced to fewer than 600,000 annually, a reduction of more than 80% over peak DDT years. By 2015, malaria-fighters once again spoke of eradicating malaria from the planet.

In contrast, India assumed the position of top producer of DDT in the world, still making it even after China and North Korea stopped making it. But malaria control in India weakened, despite greater application of DDT. The world watches as DDT, once the miracle pesticide used in anti-malaria campaigns, became instead a depleted tool, unable to stop malaria’s spread despite increasing application.

Were DDT the magic powder, or even “excellent powder” its advocates claim, India should be free of malaria, totally. Instead, Indians debate how best to get control of the disease again, and start reducing infections and deaths, again. Below is one story, rather typical of many that crop up from time to time in India news; this is from the Odisha Sun Times. (Note: Lakh is a unit in the Indian number system equal to 100,000; crore is a unit equal to 10,000,000.)

Odisha Sun Times Bureau

Bhubaneswar, Mar 15:

Odisha has earned the dubious distinction of having a hopping 36% share of all malaria cases in India and ranking third in the list of states with the most number of deaths leaving most of its neighbours way behind.

These startling revelations have been made in a report tabled by the Union Health and Family Welfare department in the Parliament.

What is more disturbing is that the number of persons getting afflicted with the disease in the state is rising every year despite the state government spending crores of rupees to arrest the spread of the disease.

The state government has been spending crores of rupees on a scheme christened ‘Mo Masari’ (“My Mosquito Net’) and has been claiming that the number of afflicted has been falling in the state. But the Central government report has exposed the hollowness of the claim.

According to the report, out of the 10.70 lakh people who were afflicted with malaria in India in the year 2014, about 3.88 lakh (36.26%) were from Odisha. In 2010, around 3.95 lakh were afflicted with the disease. The number had come down to 3.08 lakh in 2011 and had further scaled down to around 2.62 lakh in 2012, the report says.

But the number of malaria patients in Odisha is again rising at a faster pace since then, according to the Health Ministry report.

Even though the neighbouring states of Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh are identified as malaria prone states, much less people are afflicted with malaria in these states as compared to Odisha. In 2014, only 1.22lakh people were affected with the disease in Chhattisgarh while only 96,140 persons were affected by malaria in Jharkhand in the same year.

Statistics cited in the report also reveal that Odisha has left many states behind and has marched ahead of others in the matter of number of deaths due to malaria. It ranks third on this count in the country.

In the year 2014, a total of 535 persons had died of malaria across the country. Out of them 73 (13.64%) were from Odish while Tripura had the maximum number of deaths in terms of percentage at 96 (17.94%) followed by Meghalaya, another hilly state, with a toll count of 78 (14.58%).

Another disturbing fact that has emerged from the report is that out of those who have died of malaria in Odisha, 80 percent are from tribal dominated areas.

The districts of Gajapati , Kalahandi , Kandhamal, Keonjhar, Koraput, Malkangiri, Mayurbhanj, Nabarangpur, Nuapada, Rayagada and Sundargarh account for both the maximum number of deaths due to malaria and maximum number of persons afflicted with the disease.

Spread the word; friends don't allow friends to repeat history.

Posted by Ed Darrell

Posted by Ed Darrell